|

CHAPTER 16 – CHROMATIC HARMONY |

|

Chromatic Harmony has been used to add colour and expression. However, because of its opposition to Diatonic Harmony, its use can sometimes be complex. This chapter introduces the basic principles of Chromatic Harmony and the most common chords within it.

|

|

1. DIATONIC AND CHROMATIC HARMONY

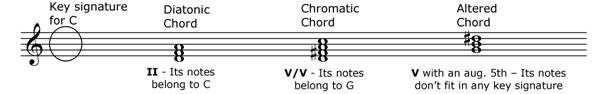

- We say that a chord is diatonic when it is constructed exclusively with notes belonging to the key signature of the current key. On the other hand, when a chord presents some accidental out of the key, it is called a chromatic chord.

- During the first centuries of the development of polyphony (11th to 14th century), the harmony used was almost exclusively diatonic. It was during the Renaissance that chromatic harmony began to be explored. Later, it remained in restricted use during the Baroque and Classical periods, but it was from Romanticism onwards that it began to be used intensively (Chopin, Brahms, Listz, Wagner, among many others), becoming a very characteristic feature of Romantic music.

- Some chromatic chords have already been presented in previous chapters. This is the case of Secondary Dominants (Chapter 7), and even of dominant 7th chords with an added minor 9th or diminished 7th chords within the major mode (Chapter 12). And don’t forget the Chromatic Non-chord Tones (Chapter 14).

2. CHROMATIC AND ALTERED HARMONY

- There are authors who speak of "altered harmony" as a subgroup of "chromatic harmony", without there being a completely clear criterion among them. Here we will apply the following distinction:

- Chromatic chords would be only those that can be generated from a different key signature than the current one. This is the case of Modal Mixture chords, Neapolitan 6th chords, and Secondary Dominants.

- On the other hand, altered chords are those whose accidentals do not fit in any key signature. This would be the case of Augmented 6th chords and chords based on an augmented triad.

Im. 16-2

- The use of the most common chromatic and altered chords in classical tonal music is detailed below.

3. MODAL MIXTURE

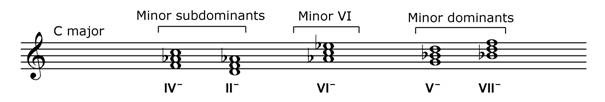

- We define Modal Mixture as the use within the Major Mode of chords that actually belong to its minor parallel key. An example, as shown in the figure below, is the use of chords belonging to C minor within the key of C Major.

Im. 16-3a

- In the example, they are ordered from more to less frequent in tonal music. The most frequent are the subdominant chords and the VI- degree, which are used similarly to their diatonic equivalents within the Basic Harmonic System, simply generating a remarkable colour change, like languor. The only exception to this "languor" is the VI- degree. Being a major chord, as opposed to its diatonic equivalent which is minor, the VI- degree has a bright sound, especially when placed in a deceptive V-VI- cadence.

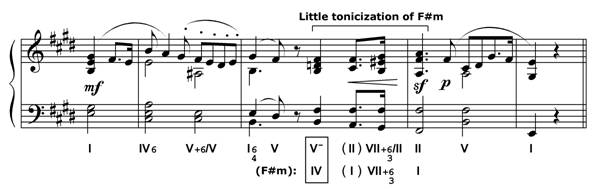

- The minor dominant chords are much more infrequent, and do not have a clear and defined function within the Basic Harmonic System. This is due to the fact that they lack a leading tone, and therefore a gravitating force towards the tonic. For this reason, they are usually associated to processes of tonicization or modulation to new tonal centres. This can be seen in the following example taken from a piece by Mendelssohn:

Im. 16-3b

Mendelssohn, Songs without words, Nº9. Op 30, 3.

- As this example shows, it is relatively common for modal mixture chords to be preceded by their major equivalent (in the example, V - V-).

4. NEAPOLITAN SIXTH CHORD

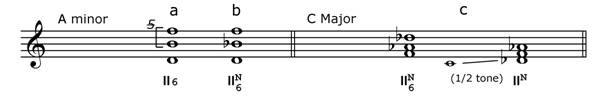

- The Neapolitan 6th chord is a II degree chord, therefore subdominant, which often appears in first inversion, hence its name.

Im. 16-4

- Its origin is in the minor mode. In order to avoid the diminished 5th interval (a), the root of the chord was sometimes flattened (b). Curiously, a major chord thus appears, with a very characteristic colour which, we stress, maintains its subdominant function.

- Later, especially in romantic music, its use was also extended to the major mode (c), even as a tonal region to which one could modulate. Within the major mode, the chord construction is identical to that of the minor mode: it is a major triad lying a semitone above the tonic note of the scale.

- In both cases, in the minor and major modes, the Neapolitan 6th chord generates a special colour, with a very intense impulse of resolution towards the dominant (or the cadential 6/4). In 4-part texture, it is common to double the third of the chord, which enhances its subdominant character.

5. AUGMENTED SIXTH CHORD

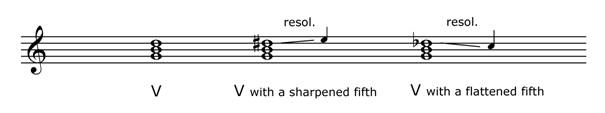

- The most common altered chords are chords with a dominant character that contain either a sharpened fifth or a flattened fifth. This means that the fifth of the chord needs to be resolved, as shown in the example:

Im. 16-5a

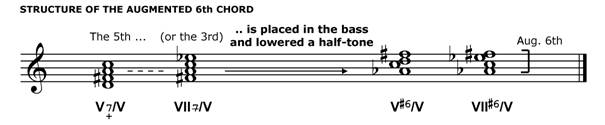

- Among the dominant chords with a flattened note, the most frequent is the one applied to the V/V with a flattened fifth (or VII/V, with a flattened third). This chord is called the Augmented 6th chord. And as can be seen in the following figure, the construction process is similar for the V/V and the VII/V:

Im. 16-05b

- In both cases, V/V and VII/V, the steps to write the augmented 6th version of the chord are the same:

1 - The 5th of the chord (in the case of V/V) or the 3rd of the chord (in the case of VII/V) is placed in the bass. In both cases it is the same note of the scale.

2 - Lower that bass note by a half-tone.

- The appearance of an augmented 6th interval between the bass note and the leading tone of the chord is what gives the chord its name.

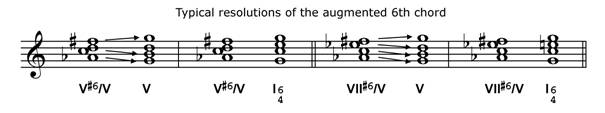

- The resolution is similar to that of any Secondary Dominant of the Dominant (V/V or VII/V), usually leading to the Dominant (V) or to a cadential 6/4. The peculiarity is that the lowered bass note acquires an intensified gravity towards the root of the Dominant (which lies a semitone below).

Im. 16-05c

- This is why the Secondary Dominant of the Dominant with augmented 6th has a very strong musical tension. This is particularly evident in the VII/V version, the most frequent, in which all its notes must be resolved!

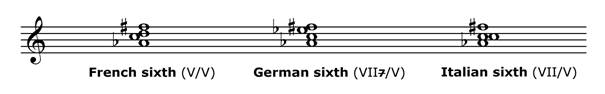

- Finally, below you will find the somewhat poetic terminology used by many authors to describe the different types of Secondary Dominant of the Dominant with Augmented 6th:

Im. 16-05d

6. AUGMENTED TRIAD

- The augmented triad, as described above, is an altered chord that arises by raising the 5th of a major triad by a semitone. It usually has a dominant function, so it is normally applied to the main dominant of the key or to secondary dominant chords.

Im.16-6a

- As can be seen above, the fifth resolves upwards to the third of the following chord, which must necessarily be a major chord.

- It is very common (examples 1, 2 and 4) for the augmented triad to be preceded by the same unaltered chord. In this situation, the augmented fifth gains the role of a chromatic passing note, which is in fact its true origin.

- Here you can see an example of a 4-part realisation, which in principle has no specific requirements, with the root doubled in the case of augmented triads:

Im.16-6b

- In this last example, we take the opportunity to show the use of an augmented chord in 1st inversion (see the V/V chord). We also have another special case, which is not very frequent: the simultaneous use of an augmented 5th and a 7th, which inevitably leads to the duplication of the 3rd in the following chord (see the final V - I).

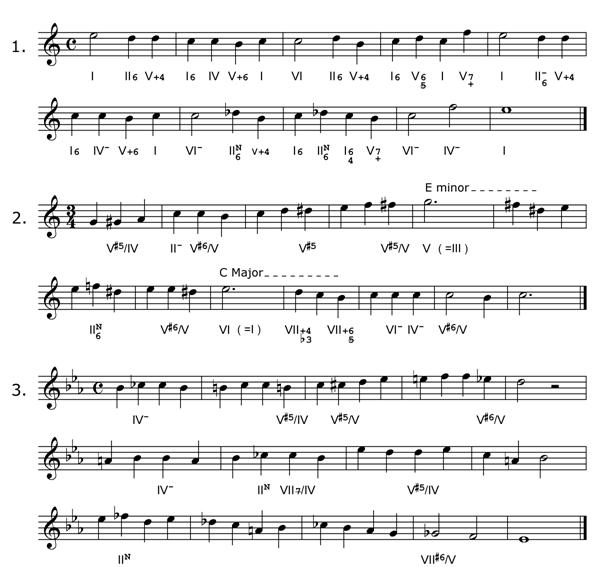

7. SUGGESTED EXERCISES

- Harmonise the following soprano lines for 4 voices, using the chords indicated. In exercise No. 3 there is a modulation to the dominant key and then back to the tonic.

4. Given the following opening of the soprano line, complete three phrases of at least six bars each. Modulate to the subdominant key in the middle phrase and, in general, make intensive use of the chords studied in this chapter.

|